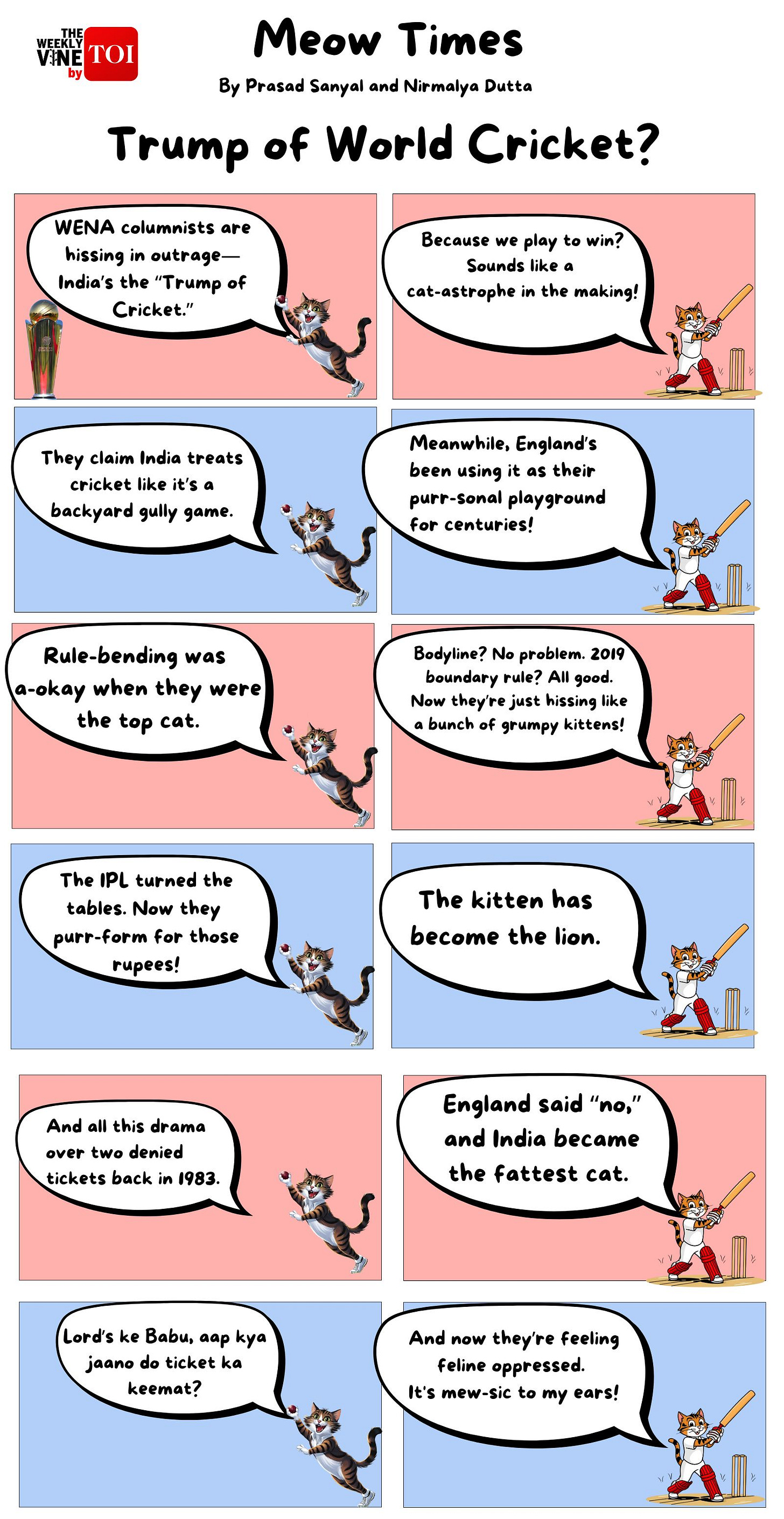

The Trump of World Cricket?

While not entirely inaccurate, the analogy is particularly amusing.

One of the more tedious tendencies of WENA columnists is their penchant for using the word “Trump” to describe anything they dislike, fail to comprehend, or cannot predict. Take, for instance, a random right-wing Hungarian politician who has been active since the 90s but is suddenly dubbed the “Trump of Hungary” simply because op-ed writers can’t be bothered to understand the world beyond their Occidental lens. The latest entrant in this overused lexicon is India, which has now been labelled the “Trump of World Cricket.”

While not entirely inaccurate, the analogy is particularly amusing. The fact of the matter is that when you see white dudes whining about India treating international cricket like its personal gully sport (and we do), remember—when you’re used to privilege, a little equality feels like oppression. To use a British phrase, the shoe is now on the other foot.

In fact, despite all its largesse, India let Pakistan host the tournament—unlike the so-called liberal West, which completely barred Russia from every sporting event. If the Indian cricket board didn’t want to make a quick buck, it could blackball Pakistan out of world cricket and threaten to cut all ties with countries that tour Pakistan. If it wanted, it could simply pull out of the 2025 Champions Trophy (instead of playing) and hold a mini-IPL, which would generate more revenue than the international tournament. But the Indian cricket board doesn’t go that far, even allowing ex-Pakistani internationals to commentate and appear on talk shows despite the fact that they have batted for Ghazwa-e-Hind—a fallaciously-interpreted fantasy about jihadists taking over the Indian subcontinent.

Simply put, it’ll be a long time before India becomes like Trump.

However, India’s role in the ICC does, in some ways, resemble America’s position in NATO—where Uncle Sam foots such a large share of the bill that Europeans are outraged when Trump asks them to contribute fairly.

Similarly, India generates more than 80% of cricket’s revenue. And much like the unwritten rules of gully cricket—where the bat owner is never out—tournament regulations are often tweaked to maximise Indian viewership. After all, if India doesn’t progress deep into the tournament, its revenue starts looking like NATO’s budget without America’s contribution.

Yes, it’s true that rules were adjusted to ensure India played all its matches in Dubai. But it’s still incredibly satisfying to read a BBC columnist complain about it—only to admit, albeit begrudgingly, that it wouldn’t be “possible to play the tournament without India.”

The thing is, like The Matrix, we’ve seen this simulation before.

Cricket has long been a sport where rules are bent to accommodate the big boys—which once meant England (and to a lesser extent, Australia). Bodyline bowling was perfectly acceptable when used to neutralise Donald Bradman’s genius, but when West Indian fast bowlers deployed the same tactics against English batsmen decades later, it suddenly became a problem. In 2019, England won the ODI World Cup thanks to the so-called boundaries rule—arguably the most arbitrary way to decide a match. During the apartheid era, England played unofficial Test matches against South Africa, moonlighting as a “Rest of the World” XI. And in 2013, the Ashes was conveniently kept outside the World Test Championship (WTC) structure to preserve its status as a high-revenue bilateral series.

Of course, today, the Ashes is an afterthought compared to the Indian Premier League—the brainchild of a man who once brought FTV to India and briefly convinced us he was dating Sushmita Sen. The IPL has reversed years of cricketing colonialism to such an extent that it’s now the white man braving Indian summers, dancing to Telugu reels, and smacking a few balls—a new form of glamorous indentured labour.

But none of this would have happened if the British hadn’t stubbornly played their Captain Russell role from Lagaan, determined to remind Indians of their place. As the story goes, in 1983, when India reached the World Cup final, BCCI President NK Salve requested a few extra complimentary passes from the Marylebone Cricket Club—only to be flatly denied. The BCCI’s young treasurer at the time, Jagmohan Dalmiya, took great offence and spent the next decade chipping away at England’s dominance, ensuring that the epicentre of cricket shifted from Lord’s to India.

To paraphrase a line from a popular Bollywood movie: “Lord’s ke Babu, aap kya jaano do ticket ka keemat.”

And as for the ever-angry columnists of the liberal-based international order, here’s a reminder: “When you are used to privilege, a little equality feels like oppression.” Or to quote the late great Bappi Lahiri, who came up with this classic during COVID: “It’s a tough time.”

Here too India continued appeasement the trademark of every political party . They brought out minority commentators to showcase this attitude