One of the oldest tropes about writing is that one must suffer for one’s art. However, my friend Kushal Mehra’s book taught me that sometimes, one has to suffer for one’s friend’s art as well.

The Sisyphean journey – fitting since Anand Ranganathan mentioned him at least 100 times during the Delhi launch event – began with reading and editing his book. It continued into his book launch event, a standing-room-only affair that was as packed as a rally at Brigade albeit without any threats to one's life or limb, at the India International Centre. The sweltering heat in the room – not only from the rambunctious discussion between some of the most loquacious orators in the non-Left spectrum – made one wonder whether it really mattered if there was a God or not, as long as ACs existed.

Jokes apart, those who follow his utterances – when he keeps a lid on his French – know that Kushal is an articulate orator, one of the finest ideological opponents of clickbait and gasbagging that masquerade as edgy content creation these days. The same leitmotif runs through his first book in which he takes an ideological journey through Indian skepticism. Think of it as the literary equivalent of Breaking Bad. Yes, there are slow moments, but the payoff is totally worth it.

Nastik: Why I am not an Atheist is a fine addition to the millennia-old Indic discourse on skepticism, a review of (and even defence) religion in this world, the difference between monotheistic and non-monotheistic faiths, and why we don’t have to choose between believing and non-believing to live a meaningful life. It also takes a deep dive into his own beliefs, and how the idea of apostasy never threatened to expel us non-believers from life into the afterlife in the Hindu way of life. It’s a journey that many of us have been through and why our atheism has never been as angry as the WENA version.

In a country, where TV debates consist largely of unwatchable blobs shouting ad hominems at each other, where intellectuals write the same article umpteen times, and utterances about religion can lead to body-part dissections, it was heartening to be in a roomful of believers willing to listen to reason and politely disagree. It was also fascinating to see many young folks there, those who are trying to find a grammar and voice to understand and argue about the world. This point about tolerance was reiterated when Anand Ranganathan – having spent the better part of the evening explaining biology and evolution to bust the notion of a god – asked the audience if anyone had converted from believing to non-believing.

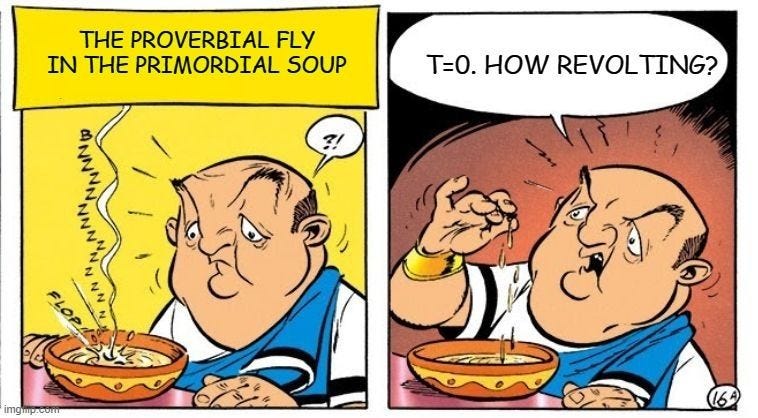

The answer from the audience – maybe they just wanted to get out of the room – was a firm NO. Of course, one could be a cynic and point out the Gregory House maxim that if one could reason with religious people, there would be no religious people. But as brilliant as the fictional Dr House was, there’s a simpler example - one that his imaginary Anglo-Saxon heritage prevents him from accessing - we don’t need to buy into the same worldview to co-exist coherently. And even though I am a firm non-believer, I’d point out that what happened at T=0 is still the proverbial fly in the primordial soup, a question that science still hasn’t been able to answer with clarity.

The T=0 Problem

Of course, as I’ve written before:

“So, what now? Will we ever know how things changed at T=0? In Test cricket, when a batsman gets out before the wee hours of the daybreak, you send a night watchman to avoid losing another wicket. Similarly, philosophy usually has to play the night watchman’s role till science comes up with an answer. Basically, metaphysics has to lay the groundwork for physics. Here’s what we have so far to explain that moment.

The first is that consciousness is a fundamental, like matter-energy – it exists and pervades all nature on its own – it is called – Panpsychism.

Another view called Promissory Materialism, coined by intolerance expert Karl Popper, says that materialists are sustained by the faith that science will redeem all promises. Science, not Christ, is their redeemer. They reason that about 100 years ago, we couldn't explain life, but now we understand life at a molecular level. Perhaps, in 50 or more years, we will be able to explain consciousness too.

The third view is that not only matter is fundamental, but it’s also elusive. In the beginning, we only had atoms, then we found electrons, protons, nuclei, and quarks, followed by the particle zoo – enough elementary particles to astonish Sherlock Holmes – and now we have superstrings and their vibrations in ten dimensions. The more we try to look at the matter, the more elusive it becomes. Perhaps, we should say that it actually is a “hard problem of matter” as well as the “hard problem of consciousness”.

Since we’ve no explanation as to how the Big Bang behaved at singularity – the uncertainty principle makes it clear that nothing can be measured exactly, and all known laws of science can work only after the expiry of what is called Planck’s Time, a point of time T > 0. We know nothing of the point of singularity, the beginning of the Big Bang. In the same way, science says life began from the primordial soup, but can't pinpoint how and when it began (when time =0).”

Either way, proverbial flies in the soup apart, the event was a reminder that both dissent and tolerance are hallmarks of our millennia-old Indic culture. And for that much, a little suffering was totally worth it.

Go ahead, buy the book. It’s totally worth your time.